I’m offering up another book review, for a title which preceded the absolute feng shui “craze” that happened in the mid-to-late 1990’s. Kwan Lau’s book, Feng Shui for Today: Arranging Your Life for Health and Wealth, was published in 1996. I am sure I was attracted to the cover art, which displays a traditional Chinese Feng Shui compass, called a luo pan.

In re-reading this thin book, I found sections I enjoyed immensely and others which will be discussed in this review. The point of these reviews is to bring out what distinguishes the feng shui books in my library from each other and to comment on theories and applications which I don’t practice myself or clarify where descriptions may be nebulous.

The author touches on some fundamental concepts which are all but missing in the flood of books which came a few years later, mostly by authors of the Black Hat School of Feng Shui. Kwan Lau mentions the foundation of Taoist thought, describing Heaven, Earth and Man Luck as our relationship with the environment and the spirit world. Later he adds that balancing one’s environment is not just done for the sake of peace and harmony in this world, but also in preparation for the afterlife. This brings a whole new meaning to the practice of Feng Shui, especially since there is so much modern-day emphasis on manipulating qi just for the sake of making more money.

He gives us more context and history of Feng Shui, along with the sage advice to choose a Feng Shui master carefully, since not all of them practice what they preach. Kwan Lau writes that his knowledge of Feng Shui came from family lineage, specifically his late grandfather Lau Baifu (1877-1941).

Stories about early Feng Shui masters, when they lived and the books they wrote is also appreciated, along with the fact that between the Tang and Song dynasties more than a hundred different “schools” were recognized and which competed with each other. By “schools,” we are not referring to physical locations; rather different styles or approaches to Feng Shui. This might be on par with the different schools of martial arts.

Next we get to a section the author titles, “Nine Stars Feng Shui.” Not to be confused with the completely separate practice of Nine Star Ki, nor the 9 stars we refer to in the Flying Star (Xuan Kong Fei Xing) School. No, what he refers to here is closer to the Eight Mansion School (Ba Zhai), but with a twist.

In virtually all descriptions of the Ba Zhai School, there are Eight House Types based on their back (sitting) direction. In other words, a house that faces east, likely “sits” west since most houses have parallel front and back walls. That house type would be called a “West House” because the back of the house is where its strength comes from. In the Ba Zhai School, the floor plan is then divided up into eight directional zones, according to an actual compass reading. Each house types then has four positive zones and four negative zones. For example, in a house that sits South, the southeast sector is one of the positive zones. But in a house that sits Northeast, the southeast is one of the negative zones. One of the goals, of course, is to dwell as much as possible in the positive zones.

The twist which Kwan Lau delivers is that the four positive zones and four negative zones in Nine Stars Feng Shui are determined based on the location of the main door and not based on the sitting direction of the house as a whole. This is not to say that the main door (a portal for qi entrance and exit) is not important. However, he uses the identical descriptions and designations for positive and negative zones as is done in the Ba Zhai School. Using the main door as the reference point and not the sitting side of the house is going to yield completely different interpretations of the same house as seen by the Ba Zhai School. Is this a mistake? Probably not, but this different interpretation is yet another example of schools which contradict each other.

He prefaces his method with insight into the Nine Stars, as representing the seven stars of the Big Dipper and its two “assistant” stars. Many aspects of Feng Shui are connected to astronomy, but not always mentioned in beginner’s books.

One of the first Feng Shui books I ever read was the first edition of The Feng Shui Handbook by Derek Walters (pub. 1991). In that book he describes the Eight Basic House types based on the facing side of the house, not the main door. As we know, not all main doors are smack in the middle of the front side of the house. Some are off to the left or right, which usually means they are in different directional zones than the facing side of the whole house. Years later, Walters came out with a newer addition of his book and corrected the error he made in how he categorized the Eight House types. He joined all the other Ba Zhai practitioners in noting that the sitting side is the real character of the house, which then designates the location of the four auspicious directions and the four inauspicious directions.

For these kinds of formulas, whether it is based on the facing side, the sitting side or the main door location, I am always very reluctant to embrace those systems, as they do not factor in timing (when the house was built). For me, this is critical data and it can change everything about how we interpret the whole house as well as the eight individual directional sectors.

From there, Kwan Lau describes what to do with each directional zone to enhance the positive energies or reduce the negatives. At first, I was disappointed to re-read about all the folk remedies he suggested for various areas, such a placing a statue here or a strand of metal coins there. However, in a way, these are mostly harmless small token items which are not likely to influence a room’s flying stars in the same way as a hundred pounds of metal or some of the more “hefty” Five Element remedies which Flying Star practitioners rely on.

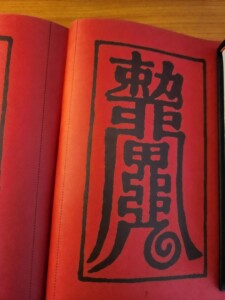

In fact, toward the end of this little book, Lau provides some actual “Fu” talismans, which he suggests taking right out of the book and using as protective symbols at the front door or wherever else needed. Needless to say, I was surprised to see this in his book which I had not read in probably 25 years. For some years now, I have been studying and making Chinese Fu talismans for clients and had never before recalled any Feng Shui book which had this information.

I have used the encyclopedia-like resource in Benebell Wen’s book, The Tao of Craft to learn the protocols of Fu-making. Like the folk remedies recommended in earlier chapters, the Fu Talisman is not considered an “element,” although the inscriptions can summon an Element or a Deity related to an Element in order to enforce the “prescription” written on the talisman. (See photo in this article of a red colored talisman from Lau’s book).

With the Fu which I create, not only do I personalize the inscriptions, but I also charge them with chants, meditation and crystals, performed on ideal days, before sending them to the recipient. Though complementary, I make sure that people know this is actually a separate practice from Feng Shui.

Some other reviewers of Feng Shui For Today have criticized how few the pages total, but back in 1996, who could have guessed that Feng Shui would become so popular just a few years later? I had the same criticism pointed at my first book by one Amazon reviewer as well. I told her to cool her jets in that I planned to write a series of books (which I did), since Feng Shui is a complex discipline which cannot be discussed in its entirety in just one book. Nor is there any App which will take the place of seasoned professional.

Author: Kartar Diamond

Company: Feng Shui Solutions ®

From the Feng Shui Theory Blog Series